“Mami, I’ve stolen a word & and it’s brought me closer

to you—…” A Review of Roberto Carlos Garcia’s [Elegies]

Unapologetically vulnerable and intimate, [Elegies], Roberto Carlos Garcia’s third release, peels back the layers of language and culture to thread a story of love, loss, and grief. Brilliant in its evocativeness, urgency, and penmanship, the compilation of lyrical elegies unwraps with nuance and complexity and gifts us with the necessary conversation of what love is/can be for a Black boy/man.

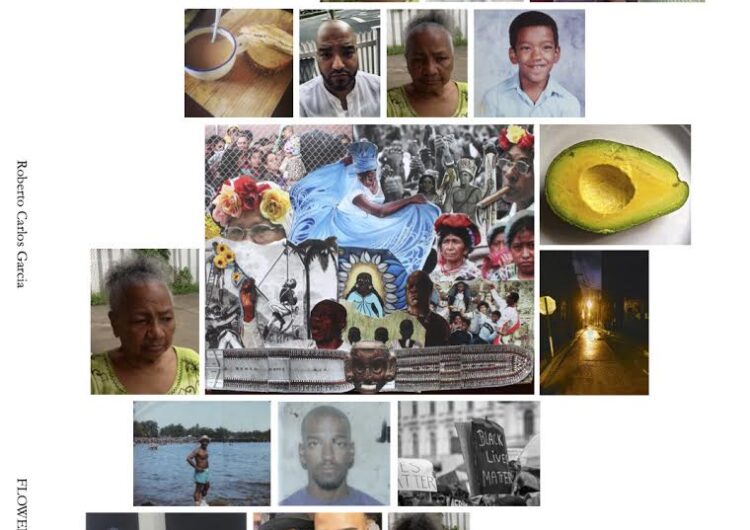

When Garcia dropped [Elegies], December 2020, we were deep into the pandemic, death was expressed in numbers and we lost track of the people behind those numbers. The whole world felt like a morgue. I let the book sit on my coffee table, and told myself, “I’ll read it tomorrow.” Then I sobbed every time I picked it up at stared at the cover, a collage of his beloveds— people, places, objects, past selves—, a living archive, an altar. The cover of [Elegies] is its own story; vibrant, enchanting, all the while crushing. A prelude of sorts. Before you even open the book, there he is, Black boy/man, his love/loss, his joy/grief. Un museo de recuerdos and history. On brand for Garcia to make such an entrance (see the cover for his second poetry collection, black/Maybe: An Afro Lyric).

The title, contained inside brackets, creates a feeling of entrapment and desasosiego. A metaphor that echoes itself into despair. This choice is deliberate and poignant. On a recent interview for The Rumpus, Garcia talks about this decision, “…visually, I like the representation of trying to contain grief. Containing grief is something I tried to do by using traditional and nontraditional forms.”

This shit is genius and rejects simplicity. Brackets as an aside showing the way grief is always interrupting us, is unavoidable and everywhere, the way grief is also a trap. Garcia writes grief with piercing precision, avoiding waste, and using poetry to carve out the experience in a clear voice. A voice that shifts between devastation and joy, and often even marries the two. And isn’t grief just that? Un huracán de sentimientos encontrados.

*

“Wasup macho-man? You good hombre?”

In its most tender moments, [Elegies] introduces us to Mami, the source of Garcia’s elegiac love and muse. Su amor del negrito. These lines from Willie Perdomo’s poem, “Unemployed Mami,” infused in Garcia’s mixtape form resonate, “Even though she don’t have a job, Mami still/ works hard. The last 23 years of her life have been/ spent teaching a poet & killing generations/ of cockroaches with sky-blue plastic slippers.” The remnants of Mami’s life and death are the backbone of the book. Yet, within this intimacy, we find our own stories: our abuelitas’ beehives and big city dreams, our hoods and our corners, the rent-controlled apartments our mothers turned into homes, where they loved us “with the same love they received, or hopefully/ better.” In Garcia’s matriarchal upbringing, he learned about manhood from the women around him and the echoes of the men that left them. We embark on this journey in poems like “To a Young Man on His First Period”, where a boy/man learns how to bleed, and “Elegy for my Pop”, where we witness that boy/man extend the forgiveness he was never asked for. In each elegy, Garcia decolonizes Western models of love like the nuclear family and patriarchal toxic masculinity. In each elegy, Garcia reveals the tender sorrow of a Black man/boy in the face of heartbreak and loss.

I love the spaces where book plays with the quotidian and delicately details the pieces that make the poet. Garcia pulls poetry from quiet moments that escape us, from the hours we cannot keep, but still tick on our clocks. Those small moments that often come back to our palates; their bitter nostalgia or sweet saudade. As a storyteller, Garcia, is not afraid of difficult love, unthreading his subjects to show their humanity. In “Elegy for Bill Withers,” for example, he smoothly elegizes Bill Withers’ legend, a painful post break-up debris, and the saving grace of weekend visitations with his daughter. There is something soul-warming about honoring our small battles—wins and losses, something validating about naming them.

*

“The whole world is grieving & I think only of your death.”

Yet, [Elegies] goes beyond this intimacy. Roberto pulls us into our collective experience of grief and fear as Black people. In the book’s lone prose offering, “10 Minutes of Terror,” Garcia recounts a traffic stop that is anything but routine. He writes:

Roberto Carlos García

“I drove on, my mind running through possible scenarios: will he make a U-turn and come at me full speed, is he calling in other cars to cut me off up ahead, should I speed up and put as much distance between us as possible.”

I too replay countless scenarios in my head when I feel or see police presence. In all of those scenarios, no matter how many times I reimagine them, I end up dead. In all of those scenarios no one is held accountable for taking my life. Garcia is keenly aware of himself and the ways in which his Black boy/man body occupies space. His writing centers on his Negritude and its implications. [Elegies] is a timely rendition of our collective mourning during a pandemic to which we, Black people, are especially vulnerable. In [Elegies] my own loss finds a mirror. There is nuance in elegizing our ancestors, our icons, our journeys, our survival, our beloveds, our past selves. Grief is not just personal, but political. It is an act of resistance where elegy turns into ode and ode becomes a celebration.

*

“I come from a people who remember such things who tell

stories inside the stories we are told. And, so do you.

And that’s word, word to everything I love.”

In [Elegies], Roberto introduces us to the mixtape, a poetic form that cracks the cento wide open by introducing lines from fiction, nonfiction, rap lyrics, and other forms of literature. The form evinces Garcia’s cultural, linguistic and literary mélange. It breaks the euro-centric restraints of the cento by recognizing and introducing the literary richness of Black popular culture. It allows room for Garcia to celebrate his vernacular languages and flaunt his poetic artistry. The mixtape poems pulse with music on every line. Each poem introduces a new melody, a new sound, a new beat. Each poem opens a new vista, a new perspective for the reader to connect to. It is dope to see how Garcia reimagines lines by icons like Jay-Z and Kendrick Lamar and is able to deliver them with renewed energy. The form is an ode to 90’s hip-hop’s mixtape culture. It evokes a sense of nostalgia and I travel back to 1994. I am holding a yellow walk-man el primo Rainy brought from Los Paises and he is teaching me how to rewind and fast-forward to where the beat drops. The mixtape is a masterful way to bring the cento to the hood.

[Elegies] finds me on the couch, living through the second season of a pandemic that has taken as much as it has given. I scout online for vaccine appointments for Mamá. I worry about Mami’s Covid exposure at her hospital job. I call home every other day and text every morning. I even started calling Papi and mis hermanos from that side. I am scared, but love and life keep happening around me. I look out the window at the crack house on the corner where every day lovers find love against all odds. Here, [Elegies] is love, and what love can be after love. Here, [Elegies] is medicine; un unguento, vivaporú para el alma.

“Love—through the gentle pain of experience,

because birds never ask is this song rivers

never ask is the ocean this way.”

Ser Álida is a Queer Afro-Dominican writer and educator living in Jackson, Mississippi. Her work dissects ideas of identity—blackness, queerness, womanhood, Dominicanidad, and language. In 2018, an early edit of her poem diary of a mad black woman: Inaugural Address 2016 was a finalist for the ACLU of Mississippi Fight for Freedom competition. A lover of Black people and malecón sunsets, when she’s not teaching, she’s most commonly found daydreaming about Bachata, romo and colmadón Sundays. She is a 2021-2024 MFA Candidate in Fiction at the University of Mississippi.

Ser Álida is a Queer Afro-Dominican writer and educator living in Jackson, Mississippi. Her work dissects ideas of identity—blackness, queerness, womanhood, Dominicanidad, and language. In 2018, an early edit of her poem diary of a mad black woman: Inaugural Address 2016 was a finalist for the ACLU of Mississippi Fight for Freedom competition. A lover of Black people and malecón sunsets, when she’s not teaching, she’s most commonly found daydreaming about Bachata, romo and colmadón Sundays. She is a 2021-2024 MFA Candidate in Fiction at the University of Mississippi.