“Okay, folks, please take a seat and get comfortable. We’re starting the week with another lesson designed to start some shit!” The students erupt in laughter following Professor Velazquez’s melodramatic greeting. The professor, wearing a signature Yankees jacket, scruffy sneakers, unkempt hair, and exuding a piercing gaze, has a knack for stirring the pot. “Let’s spark some lively discussions among your classmates.” The room vibrates with scattered murmurs of agreement, knowing deep down, that things are about to get interesting.

This creative writing course is a campus favorite, challenging students to step beyond their comfort zones and engage in deep, critical thinking. A hush fell over the room, the earlier laughter dying down leaving only the electric hum of anticipation as eyes met across the silent space. Just as the professor mentioned, it’s about to get real. Bueno, it’s time to roll up the sleeves and take part in the intense discussions that are always a hallmark of this classroom.

At the front of the room, the chalkboard bears the traces of past lessons, the faint outline of erased words haunting its surface, sets the stage. Professor Velazquez proceeds, “Last week, we agreed that today we would delve into the challenges individuals face when they are stereotyped, pigeonholed into specific categories. For example, the assumption that someone of a certain background or ethnicity should conform to a set mold, as Tanya pointed out last week, checks off certain boxes.”

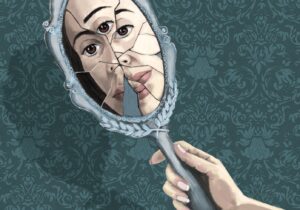

My classmates are all intently engaged. Several students lean forward, their eyes narrowing in focus, while others exchange quick, knowing glances. Ruth, known for being a provocateur, lifts her head and interjects with a smirk, “I hate being labeled as stubborn or a troublemaker when I should be celebrated for being an independent thinker.” She sweeps her gaze across the room, ensuring that her judgmental remark lands on some of us in the classroom. Perhaps some in the room harbor a hint of admiration for her audacious personality, while others, including myself, view her actions with a glimmer of annoyance, simultaneously wondering: Is there a vulnerability or insecurity driving her behavior? Is there a conflict between her public persona and her private self? But isn’t assuming that also a way of confining Ruth to a box? I hope the professor encourages us to challenge these assumptions, or perhaps it will be Ruth herself who starts to question her own identity and how she perceives others.

Leroy: (with a chuckle) “I get boxed in as the ‘athletic guy’ all the time just because I’m African American. It’s like my interest in poetry is invisible to all.” The tap-tap-tapping of Ayesha’s pen against her notebook echoes a rhythmic beat, a soundtrack to the internal conflict, her words reveal; “It’s instinctive though, isn’t it? To categorize people, I mean. Like, we talk a big game about not stereotyping, but it’s hardwired in us.” Ruth: “But that’s the trap, Ayesha. It’s like we’re programmed to label – dizque me stubborn, troublemaker.” (She rolls her eyes) “Labels are a lazy way to understand complex beings.”

Sunlight streams through the high windows, casting long, dramatic shadows across the floor and lending a weighty significance to the proceedings. “These stereotypes, despite being seemingly benign, can also be restrictive, problematic, and perpetuate harmful biases. Most of us here concur that we must consistently challenge these thought patterns and dismantle them, you know break down the mental borders,” Professor Velazquez continues.

As the professor’s words echoed in the room, a sudden shift occurred. The door creaks open, and in walks, a new student dressed in an eclectic mix of styles, an embodiment of defiance against any single label. Her presence seems to cast a new energy into the room, making the discussion about stereotypes even more poignant. My classmates had just spent the last few minutes affirming their commitment to dismantling stereotyping, vying for a world free of judgments and biases “We are warriors deflecting stereotypes and biases,” Noel exclaimed at one point. Yet, now they viewed this new student as an intruder into our space, as “another.”

The professor, slightly taken aback, regained his composure and gestured towards the empty seat next to Ruth. “Welcome, we’re discussing the impact of stereotyping. Feel free to jump in,” said Velazquez, with a welcoming nod.

The new student, who introduces herself as Eliza, pauses for a brief moment taking the opportunity to survey her surroundings, carefully looking over the other students who are gathered here. She calmly absorbs their expressions of surprise and curiosity. Each face in the room holds a unique story, with experiences and preconceived notions, all momentarily focused on her. She speaks, and there is a compelling mixture of serenity and strength in her voice. “I believe that our engagement with stereotypes isn’t merely a passive experience—where we find ourselves victimized by the restrictive views of others—but rather, we play an active role in crafting the very cages that define us,” she declares, introducing a concept that seemed to hover between philosophical musings and sociological critique.

Oh yeah, Eliza noticed my classmates judging her and she is determined to confront their preconceptions and challenge their assumptions, you know call them out on their bullshit. The class, once a hive of activity, now resembles a sanctuary of thought, where the only movement is the flicker of understanding passing over young faces, the only sound, the quiet thud of old beliefs being dismantled. Her perspective was not only insightful but verged on the subversive, offering a fresh lens through which to view an old subject. It was a perspective that jolted the class out of their intellectual complacency.

Professor Velazquez, usually the one steering the discourse, is intrigued, and somewhat challenged by this new dynamic. Yet, he recognized the value of this shift and the potential growth it promised. This was a seminal moment, an educational pivot where roles blurred, and learning became a shared journey. Professor Velazquez: (Clapping his hands gently) “Well articulated, Eliza. What you’ve just expressed, this keen awareness, is the essence of what I urge you to capture today. I want you to channel the depth of your convictions, the defiance of simple categorization, and the rich humanity that lies beyond the superficial labels we so readily assign,” he exhorted.

Maartje: “Sometimes I wonder if we stereotype ourselves without even realizing it. Do I act a certain way because it’s me, or because it’s what’s expected of me?”

Thomas: “It’s a cycle, isn’t it? We’re labeled, we rebel or conform, and then we label ourselves in the process. The question is, how do we break it?”

With the dialogue now open and the intellectual landscape of the classroom reshaped by Eliza’s contributions, Professor Velazquez seamlessly wove his points into the broader fabric of the discussion. “Stereotypes,” he expanded, “as Eliza so aptly highlighted, are merely societal impositions. They are also reflections of our internal dialogues and the narratives we subscribe to. They are the fortresses we inadvertently build around our identities, often without conscious thought,” he continued, drawing the class into a deeper exploration of the topic at hand.

“We are then drawn to a mentality of belonging to certain groups or tribes” he explained. He brought up Henri Tajfel, the Polish psychologist and a survivor of World War II, who, in the 1960s, conducted minimal group paradigm experiments to delve into the roots of discrimination. Tajfel demonstrated how people, assigned to groups by something as arbitrary as a coin toss, would nonetheless favor their own when allocating points or resources. “We simply don’t harbor as much empathy for those we perceive as ‘other,” he said, his voice trailing off thoughtfully.

Professor Velazquez pauses, his gaze drifts towards the window, where a group of students on the quad below were engaging in what appeared to be a heated debate. Their distant voices, though indistinct, carried the unmistakable cadence of passion and protest. The sight seems to stir something within him. “You know,” he began again, turning back to the class, “The human mind is intricately wired for tribalism. It’s an evolutionary relic, a mechanism that once ensured our survival, but now, it often underpins the divisions we see in society.”

Professor Velazquez adds, “We all were trained to see others—and ourselves—as members of distinct groups defined by race, gender, and other socially significant factors, and told that those groups are eternally engaged in a zero-sum conflict over status and resources.” He walks slowly back to his desk, allowing the words to sink in, his demeanor a blend of lecturer and philosopher.

The professor rests on the desk, with a relaxed posture yet commanding. “When we emphasize and magnify group distinctions based on race, gender, and other factors, we must ask ourselves: are we nurturing a culture of division or dialogue?”

Professor Velazquez surveys the room, his eyes meeting those of his students, searching, challenging. “This is not merely academic musing,” he continues. “It is the fabric of the society in which we live, breathe, and will one day lead. So, I pose to you the question: How do we navigate these distinctions to foster unity rather than discord?”

The creak of chairs and a few coughs punctuate the tense silence that followed his provocative question. The question hangs in the air, an invitation to not only ponder but to participate in the shaping of an answer. The debate on the quad, now a distant symphony of civil discourse, continued to rage on—a mirror to the intellectual challenge that now lay before the class.

Maria: (leaning back with a thoughtful expression) “This whole idea of breaking stereotypes, it’s like we’re all trying to escape a maze we’ve built around ourselves. “That’s the real trap, isn’t it? We become actors in roles we never auditioned for.”

Ayesha: “And the script gets written without our consent. It’s frustrating.”

Leroy: “But that’s the point of discussions like these, right? To rewrite our scripts.”

Ruth: (Interjecting with a smirk) “Looks like we’re all in the same boat. Maybe we should start wearing signs saying, ‘Expect the unexpected’ or ‘Stereotype me not’.”

Professor Velazquez: (With a knowing smile) “Now that’s a movement I’d endorse!”

Eliza: (With an encouraging nod) “Exactly. It’s about owning our narratives and being the authors of our own stories.”

We are now nearing the end, as the clock strikes 2:45 pm, and with it, a twist unfolds. Professor Velazquez, wearing a sly grin, announces, “Eliza isn’t a new student; she’s a graduate and a former student of mine. Today’s lesson revolved around challenging assumptions and expectations. Eliza here graciously agreed to help us demonstrate how swiftly we tend to leap to conclusions based solely on appearances and initial impressions.”

The class found themselves stunned. This revelation altered the entire dynamic. It was no longer just a discussion; it transformed into a real-time illustration of the day’s lesson. Professor Velazquez: (smiling) “See, what Eliza brought to the table today is a reflection of what we need to do. Challenge stereotyping and pigeonholed culture, dismantle the biases inside and out.”

My classmates and I quickly realized that we had unknowingly participated in an experiment that exposed our own biases. Today’s lesson wasn’t just about writing or creativity. It was about seeing and appreciating the hidden depths in others, about the stories we all carry within us, waiting to be told. There was an air of introspection and a newfound understanding of the subtle complexities of stereotypes. Professor Velazquez’s lessons were always unconventional, but today, we experienced something truly exceptional.

Leroy: “Man, the lesson today was deeper than just academic learning. It makes me question how many other assumptions I’ve made without even realizing it.”

Basheera: “So true. The question is, what do we do with this insight? How do we change the narrative?”

Maartje: “By living our truth, I guess. By being brave enough to be ourselves, even when the world tries to fit us into neat little boxes.”

Ayesha: “Shiiiiiiit. And maybe, just maybe, we’ll help others find their way out of the dvisiness too.”

As my classmates left the classroom, the atmosphere was different from when we started the lesson; and I will carry with me a new perspective on the complexities of characters, and perhaps, of each other. But another twist became apparent when I stumbled upon a rather intriguing detail: a paper labeled “Experiment 1” resting on the professor’s desk. This discovery raised an unsettling question in my mind. Damn, is the entire course, not just this lesson, part of a larger social experiment conducted by Professor Velazquez? Studying the evolution of students’ perceptions and biases in a controlled environment? Fuck! Should I share this revelation with my classmates? Would it cause them to question every interaction and lesson they encounter throughout the semester, potentially missing the bigger picture?

I think I will refrain from drawing any conclusions for now and see what the next classroom session brings about the next time. In the end, I thought the lesson was clear: understanding and empathy are powerful tools for dismantling the barriers of stereotypes, bridging the mental divides—something we dearly need in these times.

Edwin Rosario Mazara is the founder of Spanglish Voces, a non-profit promoting community building through the arts. He also founded La Sala Talks, an outlet that communicates diverse perspectives within our cultures. Currently serves as a Communications Director at the NY State Senate—an activist who loves reading, la música & conversations & las miles de historias de los desconocidos.