At first he didn’t think anything of it. Everybody falls sometimes. And especially Eduardo, who was always writing some song at the least opportune time. At a family gathering. When he was kissing his girl and suddenly had to jot down another line that popped into his head. Or when they asked him a question in class, and he heard the note he had been searching for everywhere, even in his dreams.

“If you keep up this music nonsense, you won’t get very far,” the father scolded. “Study something that will be useful to you when we’re not around anymore. We’re getting old, hijo. Who do you know that can support themselves this way?”

Eduardo hushed him, giving him a kiss on his bald head. Don’t be a grouch, papá. Didn’t you write poems for mamá? Those passionate letters she read out loud to her friends. And what about the acrostic poems and speeches you write for birthdays and funerals? Who do you think I got the writing bug from?

“What I do is a hobby. You’re a hopeless dreamer and you spend all your time thinking about writing. Soon you’ll be done with college, and I don’t know if you’ve made good use of your time there.”

He started to worry when the falls became frequent. And even more when, one day, his fingers failed him. Not due to distraction or lack of skill. They didn’t respond when he tried to play a song. They stiffened on the guitar strings, and he had to remove them with his other hand. Scared to death. Fearing that it could be what he thought it was.

Once he had gone with his Aunt Nelly to a march of men and women who suffered from the disease. With a mix of terror and admiration, he watched them move down Abancay Avenue. On foot. In wheelchairs, pushed by their mothers. With the help of a nurse.

“It isn’t hereditary,” she told him that day. “In some cases, it develops in adolescence. But in a lot of others the illness doesn’t manifest itself until age twenty or thirty. When the onset is sudden, they die quickly. Their own bodies start to turn on them. Everything in them atrophies until the machine stops working.”

“And the ones participating in the march? Will they recover?”

“These are the most puzzling ones. They’ve survived all their flare-ups, but death still stalks them around every corner. Meanwhile, they’re here. With their heads held high and their muscles numb. Clinging to life, even though someone is holding them up with a strap.”

Aunt Nelly spoke of them with total naturalness, used to seeing worse things in the school for people with functional diversity issues. Cerebral palsy, for example. The effects of being born with one chromosome too few. Or having one too many. When you’re deprived of oxygen for a few minutes after you’re born, causing irreparable damage. He, on the other hand, couldn’t sleep that night. He imagined them beautiful and slender. Doctors. Architects. With kids and dogs. With life suddenly truncated by the appearance of this damned disease.

“I don’t think that you have it,” the doctor reassured him several weeks later when he finally decided to do something about it. “You’re young and, apart from these isolated incidents, you’re in pretty good shape. We’ll do a blood test to rule it out.”

He had the necessary tests done over the course of several days. Always fasting and with absolute faith in his doctor. Dr. Bioy was right. He couldn’t have it. His jaws fit together squarely, as they had before. His movements were coordinated, and his fingers hadn’t failed him again. Nothing but a couple of stumbles, without falling all the way to the ground.

“It’s lack of sleep, hijo. How could you not be jittery when you spend all night writing? Do you think I don’t see the light shining through the crack under your door?”

“Now you spy on me, mamá?”

“I should. It worries me to see you like this. Personally, I think you’re anemic. All that songwriting is going to dry out your brain. And on top of that you write songs for your friends who don’t pay you a cent.”

It had to be that. Anemia. Lack of sleep.

“If you keep on going like this, you’re going to give yourself a burnout that will leave you dimwitted, like Coquito Arroyo. Remember?”

Everyone in the neighborhood knew that Arroyo had wound up like that after an overdose, except for his parents who kept up the story of the burnout. Out of embarrassment. But starting tomorrow he would sleep more hours and do everything possible to save the academic year. He couldn’t fool around for the rest of his life, writing songs for his buddies to sing in dive bars. Publishing his poems in local magazines. Writing random articles. He had to study something practical. Get a three-year degree so he could support himself and focus on his writing. Wasn’t he destined to become a poet?

He started writing songs to win over Giovanna. At age fourteen. Even though he had a thin voice with few charms, she liked his cheesy lines. Because of your love I am loving, / delirious, the contours of the moon. The youngest in his class, he had already grown a pair, and he told her how he felt in front of all his classmates.

“I’m going to say yes to you, Barnuevo,” she said after several attempts. “But the day you start writing songs for another girl, I’ll kill you.” She was taller than him, had curly hair, big eyes, and long, dreamy eyelashes.

How many songs did he write for her in those years? The poet-musician had lost count a long time ago. Or of the lines that he composed for Julia and Carola. Or for Silvana Anchaigua. But in his sleepless nights, he would take out his scribbles, sing them under his breath, fix a word or two, and put them away again. If I die tomorrow, he’d say to his father, gather up all my poems and publish them. Don’t underestimate me, viejo. With my little poems and songs, I’m gonna make history.

His father was proud of him, though he always begged him to stop living with his head in the clouds. Deep down he would have liked to have done the same and not have gone into accounting. Maybe he should have asked more of his son, but Eduardo was his only child and he had the right to indulge him. Soon he would find his way. Soon he would start working for real.

“What do you mean you don’t know what I have?”

“There are unexplained cases, Eduardo,” Dr. Bioy responded, downcast. With his glasses in his hand.

“And my symptoms? I keep falling. My hand is unsteady when I write. I’ve put a chair in the shower just in case.”

“The only thing I can tell you is that my whole team is analyzing your case. For now, all we can do is rule out possible illnesses with new tests. You’re free to ask for a second opinion. In Houston, where the medical field is very advanced. Or in Switzerland, where there are hundreds of similar cases. But there they will tell you the same thing. I’ve been doing this a long time and your medical file is a Gordian knot.”

They tried everything. In the United States and in their home. Traditional medicine and alternative. Needles and shots. Even a chemotherapy session that left him feeling like a wet rag, at the advice of an expert. Spiritual cleansings with animals sacrificed on his chest. Stomach pumpings and meditation. But nothing worked.

“Stop wasting your money, papá,” the son said to him with extreme difficulty. But Don Ángel Barnuevo was determined to save his son no matter what, refusing to see that, with each treatment, he got worse.

“Don’t you worry about that,” the mother assured him. “I have faith that soon we’re going to get to the bottom of this and the doctors are going to leave you feeling like new. You have the entire Parish of San Alfonso praying for you. And the Sisters of the Sacred Heart dedicate their evening prayers to you, too.”

One night of restless sleep, he woke up his parents with an animal-like scream.

“I can’t feel my legs,” he tried to say. Moving his arms wildly, drooling incoherencies in the dark.

It was half true. His left leg was paralyzed. And from that point on he used a wheelchair.

Aunt Nelly visited him in the afternoons, after spending the day working with the special-needs kids. Knowing that his illness had no cure, she did everything possible to brighten his days. First, she took him to a hippie masseuse who, in addition to kneading him into a trance-like state with a wet cloth over his head, talked to him about energy and chakras and other nonsense that made Eduardo laugh. Then she took him to a Valencian physical therapist who spent the entire hour stretching Eduardo’s arms and telling him about the different kinds of rice dishes they cooked in his region. Finally, she bought him a recliner. So that he could have his legs massaged while he watched the telenovela with his mom.

“You’re spoiling him rotten, hermana,” the father told her from the entrance to the dining room. “At this rate he’ll never want to study. And he’s promised me he’ll pursue a career.”

He would say these things to his son to get him to flash one of his rare, malformed smiles. Because even though Eduardo barely spoke, and gestured with difficulty, the father wanted to believe that he was going to get well. But in the long nights, he held his wife, and together they cried, remembering the day they bought him his first guitar. The nostalgic lines that Lalo wrote for the girls he fell in love with. Full of spelling mistakes. Or the time that they refused to let him go to a party, and Eduardo, without saying a word, snuck out through the window, taking the keys to the truck with him.

In the six years that he lived like that, with flare-ups interspersed with periods of remission, the house was transformed into a reception desk, an infirmary, and an auditorium. His friends arrived at all hours of the day to take him to the park. To play him one of his songs or to watch the soccer game. Together they cheered at the top of their lungs the historic day Peru scored three goals against Chile, and they cried like boys when they lost against Brazil.

His former girlfriends fought to spend time with him. They brought him stuffed animals and movies. Or a lemon meringue pie that they had to deconstruct in the kitchen: putting it into a blender until it turned into liquid, and adding a spoonful of thickener so he could swallow it more easily.

“Thank you for coming to see him,” the mother cried when she said goodbye to them.

“How could I not, Señora, when I’m the love of his life?,” Giovanna responded to cheer her up. “Even if he’s unfaithful to me with the others that come to see him, you know that I’m still his number one.”

That’s how she loved him, selflessly, regardless of the fact that her current partner reproached her for spending entire days in her ex’s house, attending to him as if he were her patient.

After taking all kinds of samples and ruling out a score of maladies, one March morning, Dr. Bioy concluded that Eduardo was suffering from a chronic illness that attacked the white brain matter and spinal cord. A type of unknown virus that, by eroding the fatty substance that isolates the nerves, had produced a series of irreparable short circuits.

They had told him something similar in Houston a few months before, but having Bioy confirm it was a death sentence.

Don Ángel knew then that he had to publish his son’s songs and poems. Edit them. Create final copies. Compile them.

“You should wait until I die,” Eduardo said to him with a ghoulish grin. In his garbled speech.

“No, hijo. Only you can help me arrange all this. Now that I’m retired, nothing would make me happier than to be your secretary.”

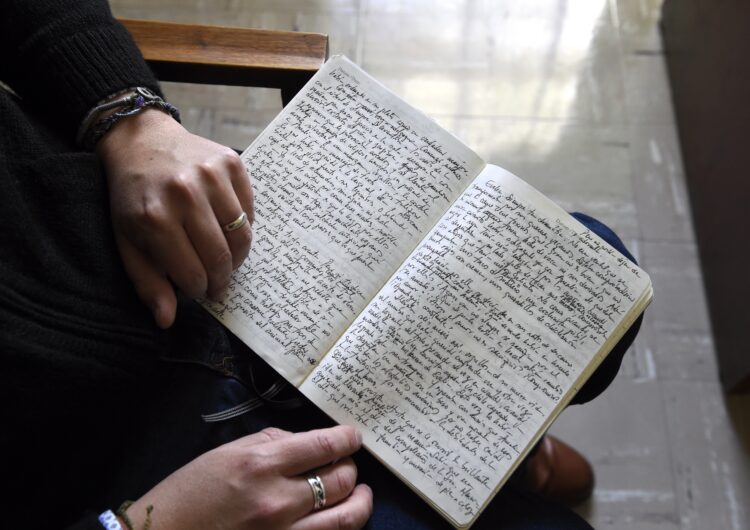

From that day on, father and son spent their best shared mornings together. After breakfast, they would settle in at the dining room table and edit, line by line, what Eduardo had written down over many years in eighteen notebooks, on the covers of his books, on bits of napkin, cardboard, envelopes, and scrap paper. Not everything was dated, but together they were able to determine which were the oldest because his handwriting had changed a lot since he won the national poetry contest for Spring Day, at age eleven.

“I wrote this one for Julia, and I was sixteen then,” he would explain to his father.

“And your friends sang this other one the summer we went to Paracas. You must have been about seventeen.”

It was tedious work, but gratifying. Reading a song aloud and correcting a word. When the ship takes us back / along the sea’s unpredictable course. Reading a line again and eliminating it entirely because it clashed with the rest of the poem. Or astonishing themselves to the point of tears upon confirming the artfulness of a poetic image, the internal rhythm of a phrase, the correct cadence… through the virulent waters / where once we drowned, like boys, / our paper boats. When the poems were bad, they put them back without bothering to fix them. Like mischievous children who hide their ugly toys under the bed. Or behind a recliner.

One day, after he had finished correcting a synalepha, he asked his father to take him to the garden.

“It’s drizzling, hijo. You’re going to get soaked.”

“I want to feel the mist,” Eduardo responded forcefully, “even if I get pneumonia and die this afternoon.”

The father understood that they had to finish editing soon, even though there were still many poems left to go over. It was more important to take his son out for walks. To take a trip to the mountains and see the snow-capped volcanoes again. The lakes of the White Mountain Range. Or to take him to see the ocean.

“You’re both crazy if you think I’m going to get behind this suicidal trip-idea,” the mother protested.

But they insisted on traveling, with the wheelchair, the medications, the thickening solutions, and everything else. She calmed down a bit when they told her they would bring Andrés, the home health nurse who lived with them to carry Eduardo from place to place, take him to the bathroom and clean him, give him a seated shower, and trim the biblical-length beard that Eduardo refused to shave.

The plan was ambitious. Drive down the coast, visiting the southern beaches. Board a puddle jumper to see ancient geoglyphs. Traverse the Central Andes to enter the jungle. And cross the Amazon River by canoe.

Just imagining them crossing mighty rivers in rudimentary vessels froze the mother’s heart. But, this far down the road, she couldn’t refuse, and she was the one who prepared their clothes and all the provisions so they wouldn’t get cold or be too hot.

“If my heart wasn’t bad, I would go with you, hijo. Even though it’s crazy, I understand that you want to do this. Promise me you’ll be very careful. And you’ll do what your father says. And you won’t skip any of your medications.”

The night before their departure, they had a small get-together. With his friends and former girlfriends. With the music that made him so happy. With guitars and a cajón. They reminisced about high school pranks. The one time he was sent to the principal’s office for writing a few lines on a desk. What are these monsters on the canvas for? / These mournful syllables? These lines? The prom with his hair slicked back. When they asked him to recite Rebellious, my soul billows to celebrate Independence Day.

It was a memorable night, full of photos and memories projected in a slideshow. Sandwiches, drinks. Heartfelt speeches. And a piñata. It seemed like everyone was saying goodbye to a grandfather who had coddled them and not a twenty-five-year-old man.

When the books arrived, the mother began to cry with happiness and emotion. He had dedicated the volume to his parents. For giving me life so many times. It’s my son’s book, she told her neighbors, promising them all a signed copy. Or a small poetry reading in the dining room.

By that time Eduardo and his father had done a bit of everything, without her knowing it. They didn’t want to give her a heart attack so that she’d force them to come back home, they joked. Together they had ridden a rollercoaster in a fishing port. They had bathed buck-naked in some thermal pools without feeling at all ashamed about their bodies. And they had even tried some marihuana cookies, which made them laugh uncontrollably and sleep like logs.

Most of the time they slept in the same room. Nestled together, like when Lalo was little and would call to his father in the middle of the night because he was afraid. Even though Andrés was always tending to Eduardo, the father wiped Eduardo’s mouth with his cloth handkerchief, he did his utmost to feed him with a special spoon, waiting as long as it took for his son to awkwardly swallow his food, and he took care to put on Eduardo’s mittens and scarf, or a blanket over his legs so he wouldn’t get cold. More than father and son, they were two old mates, happy to spend their last hours on earth together.

“I would have liked not to be sick, he confessed one restless night. To have a career. To give you grandchildren.”

They had had a day of many emotions and memorable experiences. The altitude had affected them more than they had foreseen. And they felt it in their temples. In their chests. Eduardo had trouble breathing. His father did too.

“You’ve given me so much more,” the father replied before Andrés called the ambulance. He sang Eduardo a lullaby, soothing him to sleep with love. Ignoring his own headache, the intense pressure in his right arm, the tingling throughout his whole body. He recited several of Eduardo’s poems from memory and managed to kiss his eyelids before cradling his head against his chest.

To continue the voyage together. Through other seas and other weathers… carrying aboard the weight of dreams.

* “The Weight of Dreams”, originally published in Spanish as “La carga de los sueños” is one of eleven pieces of short fiction from Oswaldo Estrada’s short-story collection Luces de emergencia (International Latino Book Awards 2020).*

Oswaldo Estrada (Santa Ana, California, 1976) is a Peruvian-American writer. He is the author of a children’s book, El secreto de los trenes (UAM, 2018), and of three collections of short stories, Luces de emergencia (Valparaíso, 2019), Las locas ilusiones y otros relatos de migración (Axiara, 2020), and Las guerras perdidas (Sudaquia 2021).

Oswaldo Estrada (Santa Ana, California, 1976) is a Peruvian-American writer. He is the author of a children’s book, El secreto de los trenes (UAM, 2018), and of three collections of short stories, Luces de emergencia (Valparaíso, 2019), Las locas ilusiones y otros relatos de migración (Axiara, 2020), and Las guerras perdidas (Sudaquia 2021).

He has edited the volume Incurables. Relatos de dolencias y males (Ars Communis, 2020) with twenty Latin American authors who live in the US. In 2020, he won two International Latino Book Awards, as well as the International Latino and Latin American Book Fair Prize from Tufts University. In 2021, he was a finalist for the Doris Betts Fiction Prize. His book Las guerras perdidas won a Gold Medal (First Place) for Best Collection of Short Stories in Spanish at the International Latino Book Awards 2022. His most recent book is the novel Tus pequeñas huellas (Suburbano, 2023). He is a professor of Latin American Literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Rebecca Garonzik (Baltimore, Maryland, 1983) is an Assistant Professor of Spanish specializing in contemporary Latin American and Latinx Literatures at The College of Wooster in Wooster, Ohio. As a literary scholar, she has published articles on Julio Cortázar, Sandra Cisneros, and Cristina Rivera Garza. Her current book project explores the literary intersections between left-wing politics and the revolutionary erotic.

Rebecca Garonzik (Baltimore, Maryland, 1983) is an Assistant Professor of Spanish specializing in contemporary Latin American and Latinx Literatures at The College of Wooster in Wooster, Ohio. As a literary scholar, she has published articles on Julio Cortázar, Sandra Cisneros, and Cristina Rivera Garza. Her current book project explores the literary intersections between left-wing politics and the revolutionary erotic.